Some animals are so special that they deserve their own day to honour them! The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is such an animal. These sharks are so iconic... so beautiful... just so completely charismatic, that they are definitely worth celebrating! So allow me to wow with a few facts about these fascinating animals on their special day...

W

World Travellers

Whale sharks swim all over the world! They have a circumglobal distribution, so can generally be found in tropical and semi-topical waters, but they also undergo incredible long-distance migrations seasonally. From attaching tags to whale sharks to track their movements, we know that they are capable of swimming as much as 67 km each day when travelling across ocean basins! Their migrations can be as long as 13,000 km! It is thought they make these long journeys to relocate between different habitats that they use for foraging and breeding (Guzman et al, 2018).

H

Hefty Size

Whale sharks are the largest fish in the oceans! Bigger than the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and even the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) (Perry et al, 2018).

It is thought that whale sharks can reach 18 metres in length and weigh as much as 60 tons! (Perry et al, 2018).

This is where whale sharks got their name, as they can be as large as many species of whales. But don't let the name fool you! Whale sharks are not whales! Whales are mammals - they are warm-blooded and breath air, but sharks are fish - cold-blooded and breathing underwater via their gills.

A

Attractive

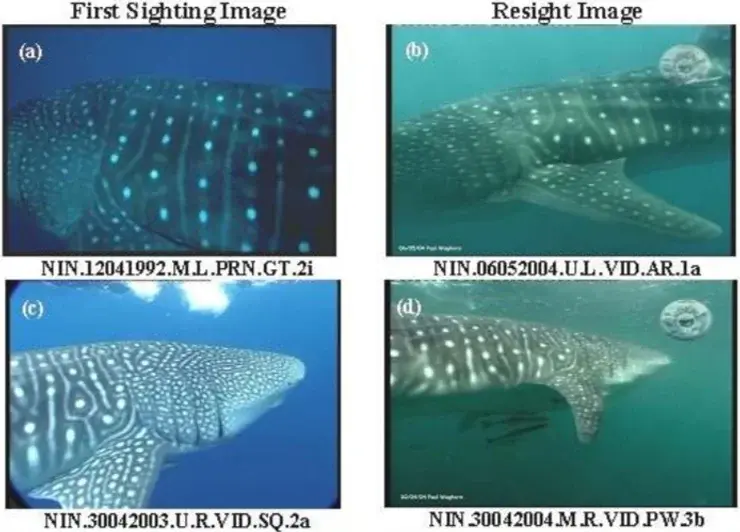

The beautiful pigmentation patterns of spots and stripes on the whale sharks' skin are one of their features which make them so iconic and recognisable. The patterns are the reason that the taxonomic group that whale sharks belong to, are known as the 'Carpet Sharks' (Speed, 2006).

These spots can be very handy for scientific research because every whale shark has a completely unique pattern, just like a human fingerprint. If we are able to images of the region on the shark's side above the pectoral fin, the unique pigmentation can be recorded in a database and be used to identify that specific sharks if it pops up somewhere else in the world. This can be very useful for tracking migrations and monitoring certain individual sharks. (To learn more, check out Seeing Spots, and you can maybe even get involved in whale shark data collection at Wildbook for Whale Sharks) (Speed, 2006).

L

Long-Lived

Whale sharks have remarkable longevity... it is thought that they can can live for as long as 130 years! They are very slow-growing and do not become sexually mature until they reach a size of at least 8 metres total length at around 25 Years of age. Therefore, they start breeding relatively late in their lives. This is very important to know because it can be critical to their conservation and management (Perry et al, 2018).

E

Eyes Full of Teeth!

Believe it or not, whale sharks have teeth in their eyes! All sharks have modified teeth which make up the skin over their whole bodies. These are known as "dermal denticles". The toughened structure and scale-like shape of these denticles are what allow shark skin to be very strong, whilst also remaining flexible (Tomita et al, 2020).

Whale sharks are the only known species which also have these structures protecting their eyes. They are known as "eye denticles". They are arranged around the the outer area of the eye to to armour it in case of strikes from debris in the water (Tomita et al, 2020). To learn more, you can check out Eyes Full of Teeth.

s

Susceptible to human Disturbance

Many human activities cause habitat degradation which affects whale sharks. For example, commercial shipping lanes can intersect migration corridors, leading to injuries or death from boat strikes. Even tourism boats, there to view the whale sharks are responsible for very serious injuries (see A Guilty Pleasure). Similarly, oil and gas drilling disrupts the whale sharks' natural environment with chemical (see Not So Slick) and "noise pollution" (see Keep the Noise Down!). Even the every-day actions of the general public can affect whale sharks, because they are especially vulnerable to littering. There have been several incidents of whale shark autopsies revealing that ingestion of plastic litter has lead to death (see 'The Worst... Beware of the Plastics!).

H

Harmless

Despite being absolutely enormous, whale sharks are incredibly docile. It is very safe for divers and snorkelers to share the water with whale sharks, with little to no risk. They are often described as gentle giants (Pierce et al, 2010).

The only real risk posed from whale sharks is that they are very, very big, so should be treated with respect. You should never approach too closely to any wild animal and the advised safe distance for whale sharks is to never encroach within 3 metres of them (Pierce et al, 2010). You would be very lucky to get so close anyway as they can swim much more quickly than us without even trying. You will definitely struggle to keep up with them, even using fins! If you would like to plan a trip to swim with whale sharks in the wild, you can check out Blue Water Dive Travel to learn about the best places and times to see them.

(Your's truly snorkelling with juvenile whale sharks in Djibouti)

A

At-Risk From Over-Fishing

Whale sharks are currently classified as 'endangered' by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This means that their populations are declining globally and they are at serious risk of becoming extinct in the wild in the near future. The greatest threat to whale sharks is fisheries. Whale sharks can be killed or injured as "bycatch" in fisheries (this means they are not the target species, but can become entangled in fishing gear used to target other commercial species) and they are also intentionally fished for their fins, which are very valuable in the Asian markets. Whale sharks have been included on CITES Appendix II since 2003. This means that the international trade of whale shark products (including live animals, fins, meat, and any other body part) is restricted and controlled globally.

R

Remarkable Reproduction

Whale sharks have the largest number of offspring of any shark species recorded... they can have as many as 300 pups at once! They are "ovoviviparous", meaning that eggs develop within the mother and she gives birth to live young (Joung et al, 1996). As if that wasn't remarkable enough, the females have some control over their pregnancies and births. Not all the offspring are born at one time, as the mother can store sperm after mating with a male, so that she can continuously produce a steady stream of pups over an extended period (Schmidt et al, 2010).

K

Krill-Eating

Whale sharks are "filter feeders". This means that they extract their microscopic food by swimming slowly through the water, drawing water into their mouth and filtering it through their "gill rakers" (stiff projections from the gill arches which act as a sieve). So, despite their enormous size, whale sharks sustain themselves purely by eating incredibly small organisms, like krill, plankton, copepods, larvae and fish eggs. In order to get enough to eat, they can filter as much as 6000 litres of water every hour!

Have I convinced you to love whale sharks?

If so, you can support their conservation by adopting a whale shark through the Shark Trust / Wildbook for Whale Sharks / The Shark Research Institute / Shark Angels. The latter also send you a fabulous whale shark plushy toy with your adoption pack! Happy days!

References

Guzman HM, Gomez CG, Hearn A & Eckert SA (2018). Longest recorded trans-Pacific migration of a whale shark (Rhincodon typus). Marine Biodiversity Records, 11. Access online.

Joung SJ, Chen CS, Clark E, Uchida S & Huang YP. (1996). The whale shark, Rhincodon typus, is a livebearer: 300 embryos found in one 'megamamma' supreme. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 46:3, 219–223.

Perry CT, Figueiredo J, Vaudo JJ, Hancock J, Rees R & Shivji M (2018). Comparing length-measurement methods and estimating growth parameters of free-swimming whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) near the South Ari Atoll, Maldives. Marine and Freshwater Research, 69:10, 1487. Access online.

Pierce SJ, Méndez-Jiménez A, Collins K, Rosero-Caidedo M & Monadjem A (2010). Developing a Code of Conduct for whale shark interactions in Mozambique. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 7:20, 782-788. Access online.

Schmidt JV, Chen CC, Sheikh SI, Meekan MG, Norman BM & Joung SJ (2010). Paternity analysis in a litter of whale shark embryos.Endangered Species Research, 12:2, 117–124. Access online.

Speed CW (2006). An information-theoretic assessment of spot-pattern matching software and its application to population estimates of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) (Doctoral dissertation, BSc thesis, Charles Darwin University, Darwin). Access online.

Tomita T, Murakumo K, Komoto S, Dove A, Kino M, Miyamoto K & Toda M (2020). Armored eyes of the whale shark, PLoS One, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235342. Access online.

By Sophie A. Maycock for SharkSpeak

LOVELY ARTICLE